Sign up for our newsletter

Sign up today to stay in the loop about the hottest deals, coolest new products, and exclusive sales.

Wahnapitae, ON P0M 3C0

Phone: 705-694-0065

Fax: 705-694-1594

Toll Free: 1-877-224-2323

Email: info@ibeadcanada.com

Mon-Sat: 10am - 6pm

Sun: 11am-5pm

Mon-Sat: 10am - 6pm

Sun: 11pm-5pm

Free Shipping on Most Orders Over $150* – Learn More >

Beaded Rosettes

Beaded Rosettes

Bells

Bells

Cabochons

Cabochons

Dolls & Acc.

Dolls & Acc.

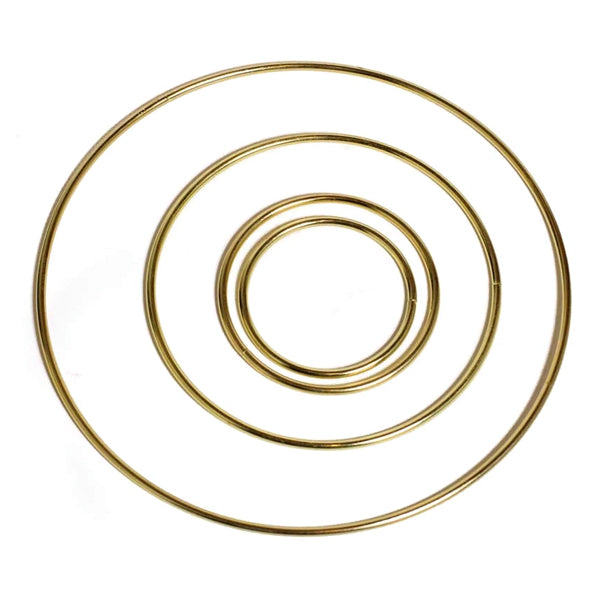

Dream Catcher Rings

Dream Catcher Rings

Drum Making

Drum Making

Flat Back Stones

Flat Back Stones

Jingle Cones

Jingle Cones

Mirrors

Mirrors

Pipe Stems

Pipe Stems

Rhinestone Banding

Rhinestone Banding

Sequins

Sequins

Sew On Stones

Sew On Stones

Beading Foundation

Beading Foundation

Crepe Soles

Crepe Soles

Elastic Cord

Elastic Cord

Fabric

Fabric

Fringe

Fringe

Ribbon

Ribbon

Trim

Trim

Bails

Bails

Bolo Tie Acc.

Bolo Tie Acc.

Bookmarks

Bookmarks

Brooch & Bar Pins

Brooch & Bar Pins

Buckles

Buckles

Buttons

Buttons

Caps & Cones

Caps & Cones

Chain Extenders

Chain Extenders

Clasps

Clasps

Crimps & Ends

Crimps & Ends

Conchos

Conchos

Connectors

Connectors

Earring Components

Earring Components

Eyelets & Snaps

Eyelets & Snaps

Findings Sets

Findings Sets

Garment Studs

Garment Studs

Hair Accessories

Hair Accessories

Head & Eye Pins

Head & Eye Pins

Jewelry Parts

Jewelry Parts

Jump & Split Rings

Jump & Split Rings

Key Chain Parts

Key Chain Parts

Mobile Phone Acc.

Mobile Phone Acc.

Safety Pins

Safety Pins

Wire Guards

Wire Guards

Feathers

Feathers

Furs & Animal Parts

Furs & Animal Parts

Leather & Rawhide

Leather & Rawhide

Cord

Cord

Chain

Chain

Leather & Suede Lace

Leather & Suede Lace

Sinew

Sinew

Thread

Thread

Jewelry Wire

Jewelry Wire

Memory Wire

Memory Wire

Shaping Wire

Shaping Wire

Bead & Craft Kits

Bead & Craft Kits

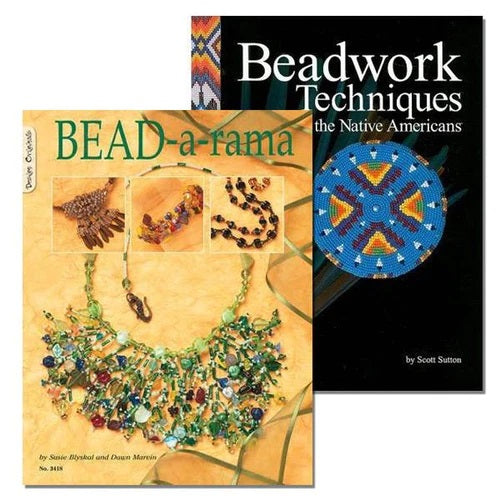

Books

Books

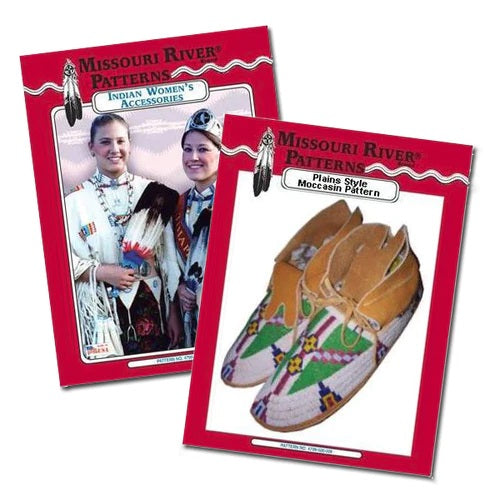

Patterns

Patterns

Displays

Displays

Gift Bags

Gift Bags

Gift Boxes

Gift Boxes

Jewelry Cards

Jewelry Cards

Organizers

Organizers

Tags, Labels & Stickers

Tags, Labels & Stickers

Zip Lock Bags

Zip Lock Bags

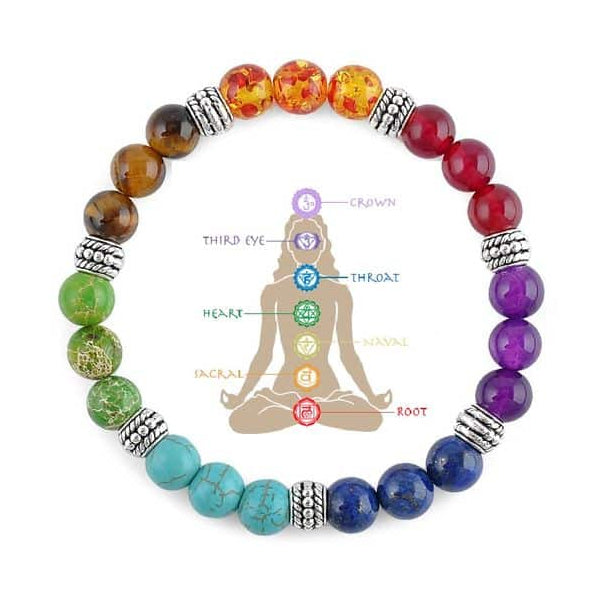

Chakra

Chakra

Healing Stones

Healing Stones

Incense & Holders

Incense & Holders

Mala Beads & Acc.

Mala Beads & Acc.

Oils & Burners

Oils & Burners

Rocks & Minerals

Rocks & Minerals

Smudging

Smudging

The History of Czech Glass Bead Making is closely allied to the impact that the First and Second World Wars, and the subsequent Cold War, had on the area as a whole. The region where glass making production is centred was formerly known as North Bohemia. Hence the descriptive term sometimes used, namely Bohemian Glass beads.

North Bohemia had been a European glass manufacturing centre since the 13th century largely because it was rich in the natural resources needed for glass making. Supplies of quartz, which was mined, and potash from the regions forests, and a by product of the wood burned to heat the glass, made it the ideal location. The cities of Jablonec, Stanovsko and Bedrichov (or modern Reichenberg) all produced glass beads, mainly for use in rosaries, but from the second half of the 16th century, when costume jewellery become fashionable, they started producing beads to be used more decoratively. The Industrial Revolution of the 19th century saw the development of machines that allowed mass production of moulded pressed glass beads, so thousands of identical beads could be produced cheaply. The mechanically shaped beads were a real innovation in terms of glass making history, as little had changed technically for many centuries. These pressed beads were not made around a traditional glass mandrel, but instead a rod forming the hole was pushed into the mould, and this meant that the hole could theoretically be placed in any position and multiple holes could be introduced. The moulds allowed complex shapes to be made and by making use of patterned canes, or the glass rods fed into the machine, the resulting beads could be elaborately coloured, giving them a slightly random appearance, even if the shape was exactly the same. In time these differing colourings, shapes and finishes resulted in Czech Glass Fire Polished beads, Czech Glass Aurora Borealis beads, Czech Glass Flower beads, and Czech Glass Swirl beads, Czech Glass Picasso beads, and Czech Glass Satin beads, with Preciosa alone now boasting 425,000 different beads and jewellery components in its range.

This sense of mass production saw the expansion of the industry and Czech Glass beads were exported around the world. However, the actual making of the Czech pressed glass beads, on the whole, remained a cottage industry, in that machines and moulds were bought and used by individuals and families who would work from home to supply the companies that would then trade the beads. As can be seen below family homes that produced glass beads could be identified quite easily by their tall chimneys and roof vents.

The image above show a typical hill side bead making operation housed in a small house with a tall chimney and roof vent. (Source: Jablonex Heritage Archive)

The image above shows a hand coloured interior view of a glass bead pressing workshop. (Source: Jablonex Heritage Archive)

Czech Glass beads manufacturers were also innovative in their salesmanship and in providing the consumer with what they wanted. Sample men travelled worldwide to speak with Czech Glass bead wholesale suppliers and determine what would sell best in each market. They then returned to Czechoslovakia and advised on specific designs for sale to these markets. This proactive approach was highly successful, increasing the sales and demand for Czech Glass beads worldwide, including from places as far and wide as Africa, Japan and Tibet.

At the end of the First World War in 1918, North Bohemia became part of Czechoslovakia. By 1928 Czechoslovakia was the largest bead exporter in the world. However, trade was then affected by the Great Depression that hit the global economy in the 1930s. This was followed by the Second World War. Immediately after the war Sudeten Germans who had lived and worked for most of their lives alongside Czechs in the Northern Bohemia region, were forcibly relocated to within the new German borders, primarily because of their allegiance to the Nazi regime during the war years. Those who were glass bead makers took their skills with them. Many resettled in the town of Neu Gablonz which was so named in honour of the bead makers. In turn Jablonec was renamed Jablonec nad Nisou.

From 1948 Czechoslovakia had a Communist government who did not see costume jewellery production or glass bead making as approved industries. However, in 1958, five years after the death of Stalin, they restarted the industry in an effort to trade out of Czechoslovakia in return for hard currency to support the faltering economy. In doing so the Communists nationalized the industry, which meant production became factory based. This single state run monopoly, Jablonex, controlled all exports out of Czechoslovakia involving both glass and glass beads, where previously at its height there had been over 2,000 agents exporting glass.

The montage image above shows an exterior and two interior shots of part of the Jablonex Factory complex in Jablonec nad Nisou (Source: Architect Drofa)

Although not widely publicized for obvious reasons, penal labour was used at the core of bead making production and jewellery assembly in Communist Czechoslovakia. Factory facilities were setup in prisons around the Jablonec area, such as Valdice prison which was formerly a monastery, and at the time had capacity to hold 2,600 inmates, including political prisoners.

An aerial view of the Valdice prison complex with the former monastery building at its centre (Source: Jiří Berger, MF DNES)

Each prison facility would have production targets, with individual prisoners assigned to bead production expected to produce 30 to 40 kg of beads a day. Prisoners also assembled costume jewellery, necklaces, artificial flowers, chandeliers and rosaries intended for worldwide distribution under the banner of Jablonex. Just when this harsh and often intensive practice ended, post Communist era, is not easy to establish.

The Velvet Revolution of 1989 saw the end of Communist control. Czechoslovakia split into two countries, the Czech Republic and Slovakia, with the region that once was North Bohemia, lying within the Czech Republic.

The glass making industry in general has now been revived in the Czech Republic, and once again supplies high quality beads to the global market. Although it is the large operators like Preciosa that dominate production, both as bead and component producers, as well as primary suppliers of the glass rods used by the smaller bead making operations. Post Communism, Jablonex became a major conglomeration, but closed its doors in 1995 and sold its furnaces and large bead making equipment off to Asian glass factories. With the loss of Jablonex the area also lost its central distribution mechanism and global export know how.

There has been a return to small scale production with individuals supplying local factories, using machine methods very similar to those employed in the 19th century, but with improved technology. However, in the last five to ten years this historic cottage style of bead making has been hard hit by the dominance of the large scale producers, alongside direct competition from India and China. This overseas competition has become more of an issue as the quality of pressed and faceted beads, from China in particularly, has improved considerably. Whilst India has focussed on supplying lampwork beads, the quality of Japanese seed beads, by Toho and Miyuki, has reached such a level as to make them the seed bead of choice for the majority of seed bead workers. This is due to their range, finish but above all else the consistency of supply. Subsequently, unemployment amongst artisan bead makers and factory glass workers in the Czech Republic is running very high, with the impact of competition and recession also felt by the large scale Czech producers, who struggle to react quickly enough to trends in fashion and design.

Sign up today to stay in the loop about the hottest deals, coolest new products, and exclusive sales.

Thanks for subscribing!

This email has been registered!

Last updated: September 11, 2025

Summary of i-Bead Inc.'s Terms of Service:

Product Descriptions: i-Bead Inc. strives for accurate product information, but errors may occur. Product availability and specifications, like size, are subject to change.

Product Images: Images are for representation purposes; actual products may vary in appearance due to display settings or manufacturing differences.

Copyright & Intellectual Property: All content on the Website is owned by i-Bead Inc. or its licensors. Users are granted a limited, non-commercial license to view and print content for personal use but cannot reproduce or distribute it without permission.

Trademarks: The i-Bead name and logo are trademarks of i-Bead Inc. Unauthorized use of trademarks is prohibited.

Use of the Website: Users must comply with laws and the Terms. Account creation may be required for certain services. Users are responsible for account security and cannot engage in harmful behavior or unauthorized access.

Pricing & Availability: Prices are listed in Canadian Dollars (CAD) and are subject to change. Additional charges for taxes, shipping, and duties may apply. Out-of-stock products may be removed or delayed.

Limitation of Liability: i-Bead Inc. is not liable for any indirect damages, and the website is provided "as is" without warranties.

Privacy & Data Protection: The use of personal data is governed by the company’s Privacy Policy, which users should review.

Indemnification: Users agree to defend and hold i-Bead Inc. harmless from any legal issues arising from their use of the site or violation of the Terms.

Modifications: i-Bead Inc. can update these Terms at any time. Changes will be effective upon posting.

Governing Law: The Terms are governed by the laws of Ontario, Canada, and any disputes will be resolved in Ontario courts.

Contact Information: For questions, users can contact i-Bead Inc. at their address or via email or phone.

Summary of i-Bead Inc.'s Refund Policy:

In-Store Purchases: Items can be returned within 30 days with the original receipt for an exchange, store credit, or refund. Must be unopened and in original condition.

Online Purchases: Returns allowed within 30 days of receiving your order. Prior authorization required. Items must be unopened and in original condition.

Non-Returnable Items: Sale items, opened packages, broken strands, cut items (e.g., leather, cord), books, and special orders cannot be returned.

Restocking Fee: Returns after 30 days incur a 20% restocking fee. Clearance/discontinued items cannot be returned after 30 days.

Damaged/Defective Items: Contact customer service within 48 hours. Return shipping will be covered, and you can request a refund or replacement.

Return Instructions: Include the reason for the return, order details, and use a traceable shipping carrier. Returns must be prepaid, and customs fees are not covered.

Refund Process: Refunds will be issued after inspection, minus shipping costs, and may take 1-2 weeks to process.

For returns, the items must be in their original, unopened condition.

Summary of i-Bead Inc.'s Shipping Policy:

Shipping Methods: i-Bead uses Purolator, UPS, Canpar, and FedEx for Ground and Express shipping.

Shipping Times: Orders placed by 12:00 PM EST ship the same day; orders placed after that time ship the next business day. V.I.Bead Members get same-day shipping regardless of order volume.

Shipping Locations: We ship within Canada and to select international destinations (excluding the United States). P.O. Boxes are not eligible.

Shipping Discounts:

Tracking & Insurance: All orders include tracking. Insurance is included for orders under $100; additional coverage is available for $3 per $100.

Damage or Loss: Contact customer service within 48 hours if your order is damaged or lost during transit. Claims will be processed with the courier.

Theft: i-Bead is not responsible for theft once a package is marked as delivered. Signature confirmation is available for added security.

Delays: Delivery may be delayed due to factors like weather, rural locations, or peak seasons.

Summary of i-Bead Inc.'s Sales Tax Policy:

Canadian Residents: Sales tax is applied based on the province:

First Nations: Eligible customers may receive tax relief with the Indian Status Tax Exemption Card.

U.S. & International Orders: U.S.: Not applicable—shipping is paused. International (non-U.S.): No Canadian sales tax or VAT is charged by i-Bead; destination duties/taxes may apply.

In short, Canadian customers are taxed based on their province; U.S. orders are not available; international customers may incur destination duties/taxes.

Summary of i-Bead Inc.'s Native Status Card Policy:

Tax Exemption Eligibility: Status Card holders can qualify for GST/HST relief if:

Ontario Residents: Eligible for an 8% HST rebate on orders shipped within Ontario.

How to Apply:

Important: Misrepresentation of eligibility can result in penalties from the CRA.

In short, eligible Status Card holders can receive tax relief by following the proper procedure and submitting required documentation.

Summary of i-Bead Inc.'s Privacy Policy:

i-Bead Inc.'s Privacy Policy outlines how they collect, use, and disclose personal information. They gather data directly from users (e.g., contact details, order info, payment info) and through tracking technologies (e.g., cookies). This data is used for order processing, marketing, security, and customer support. The company may share data with third-party vendors and partners for service fulfillment, marketing, and legal compliance. Users can access, correct, or delete their data, and opt-out of marketing communications. The policy also covers data security, retention, and international transfers.

By completing the checkout process, you (the customer) acknowledge that you have read, understood, and agreed to the Terms and Conditions outlined by i-Bead Inc. Furthermore, you agree that i-Bead Inc. shall not be held liable for any delays in shipping caused by factors beyond its control, including, but not limited to, disruptions due to COVID-19, adverse weather conditions, holiday seasons, natural disasters (Acts of God), strikes, or lock-outs or any other unforeseeable events. In addition, in the event that a parcel is damaged or lost during transit, and you have not obtained additional insurance coverage, you expressly agree that i-Bead Inc. shall not be held responsible or accountable for any resultant loss, damage, or delay.

Wahnapitae, ON P0M 3C0

Phone: 705-694-0065

Fax: 705-694-1594

Toll Free: 1-877-224-2323

Email: info@ibeadcanada.com

Mon-Sat: 10am - 6pm

Sun: 11am-5pm

Mon-Sat: 10am - 6pm

Sun: 11pm-5pm